Tyler Morse is CEO and managing partner of MCR, the hospitality company he founded in 2006. Although he barely mentions his degree from Harvard Business School, this hospitality innovator proudly produces for LODGING a laundry list of the varied life work experiences he considers “a core tenet of being an effective CEO”—including that of LAX baggage handler, bank teller, car valet, busboy, and ski instructor. They, as well as some of the loftier positions he has held, are perhaps at the heart of his willingness to challenge the status quo in an industry that is ever reluctant to stray from its long-held practices—including what he calls the “free option” of booking a hotel room without penalty for cancellation, despite the cost to owners of securing and holding that reservation, sometimes only to find out too late that the credit card number is fake.

Morse entered the hotel business after receiving his MBA and becoming assistant to Barry Sternlicht, the chairman and CEO of Starwood Hotels & Resorts, contributing to Starwood’s overall corporate investment and development initiatives. He also took a turn in the cosmetics business as president of Bliss, an upscale spa and beauty products company.

Upon founding MCR 13 years ago, he built his first hotel in Huntsville, Alabama. That was followed by another in Lexington, Ky., and then others in Kalamazoo, Mich., and Savannah, Ga. “Now, we own about 90 hotels in 29 states—20 of which we built from the ground up; we also bought some, and sold about 30-40 along the way,” he says.

Morse claims what he loves most about being in the hospitality business is its complexity. “There’s just so much to it compared to the other four ‘food groups’ in the real estate world—office, retail, industrial, and multi-family apartments. They all just collect rent, but the hotel business is so dynamic; it’s also many other businesses, including branding, finance, and distribution. You have to determine how to work—or not to work—with OTAs, GDS, travel agents, and corporate business; and you have to set pricing—something that can be very different from one region to the next.”

As much as he enjoys the hotel industry, Morse believes it is ripe for change—and hopes others will emulate some of those he suggests or has already implemented.

The first concerns a troubling trend in cancellations. “Cancellations were always a thing, even when I got into the business 20 years ago, but they kept going up. Last year, 2018, they accounted for about 44 percent of all hotel reservations.” This, he says, is a significant problem in a business based on one-day leases. “It’s hard to manage your inventory when people book, then unbook, a room.” And the reason they do it, he says, is that they can; there’s no penalty. As he points out, this is not the case in the airline industry. “If you reserve an airplane ticket, you pay for it upfront, and if you don’t, they don’t give it to you. What’s more, if you need to change or cancel, there are costs associated with that.”

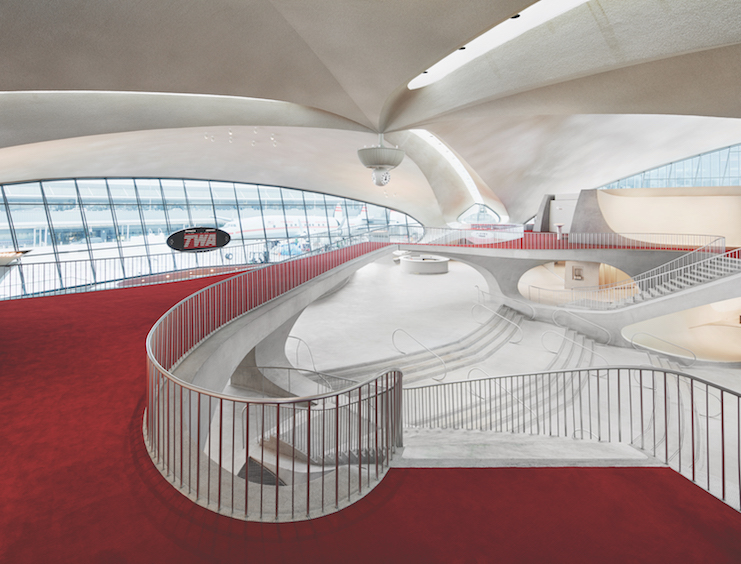

Morse admits that he was careful about his first effort to take aim at what he calls “one giant free option on the part of the consumer.” Working from a position of strength—a strong economy and a popular property in a robust market, his TWA Hotel in New York City—he implemented a modest $10 cancellation fee. “I knew I couldn’t buck the trend in the industry by coming in with a $150 cancellation fee when my competitors still had none. I just wanted to create a disincentive for that practice of booking and canceling,” he explains.

The results were positive and dramatic; cancellations at TWA dropped to 8-9 percent, a number, he says, feels right to him. “We understand that people’s plans change, but if the industry is running 44 percent and we’re running 8-9 percent, that a big win.” It’s not just that people cancel, he explains further, they can scam the system. “If you just check for the initial numbers but don’t actually run their credit card, you can find out too late that it’s a fake. Because we charge the card that 10 percent at the time of reservation, we find out then and there, not at the 3 a.m. audit; if it doesn’t check out, they don’t get their reservation.”

Morse is aware that the industry is watching and hopes more will emulate the practice, which he has not yet implemented at all properties. “I am doing it carefully and selectively. We have a unique position at JFK airport, which is a very competitive market; at TWA, the last few nights, we were at 100 percent occupancy. It’s harder to put in place terms that are less competitive than others, because the guests have that option to book without penalty.”

Related to the pain of cancellations—that is, not collecting on the promise of a room sale—concerns the pressure to and the expense of securing those reservations in the first place. “For those of us who own hotels, it’s a distribution game. We have this perishable inventory we all want to fill, so we also need to be in the business of buying reservations via marketing, OTAs, travel agents, consortia, Rosenbluth, etc.—all of which cut into our profits. We have to pay for those reservations; it’s just a question of how much.” For this reason, Morse says another practice he hopes others will emulate is moving away from the automatic use of OTAs. “We don’t use the OTAs at TWA, and it’s working out fine. But if I needed to, I could do it overnight at no risk.”

Morse also takes issue with what he regards as “how the hotel industry continues to crush its own margins indiscriminately,” including what he considers to be overly expensive luxuries, like allowing guests to text at their least expensive as well as most expensive properties. “The costs of implementing a text messaging program are astronomical. While they are in line with services you’d offer for an $800-a-night room or to a special guest, it’s not within the margin structure of a $100 a night product.”

Morse says it all boils down to being true to your value proposition. “You should instead design a product, price it appropriately, and people will enjoy it. You don’t get to text message at every hotel on the planet. That doesn’t make sense—products should be commensurate with their price point.”

Morse says his comments about value are fully in line with what he calls “the democratization of travel.” “In 1962, 60 million people flew on an airplane; last year it was 4.2 billion.” These travelers, he says, are apparently willing to accept the “sacrifices” they make to get to where they want to go. “There are now ultra-low-cost carriers that are accessible to everyone, but there are various levels of service and various price points there, as there are in hotels. I think as an industry, we need to learn from the airline industry, and stop and think about whether we can afford to offer extras that may not be in line with the value proposition— that is, do we have the resources to offer them at the $100/RevPAR level.”

“As an industry, we need to take a stronger position so people don’t continue to take advantage of us. We have this valuable asset that requires daily cleaning, maintenance, and compliance with government regulations.”

Morse recognizes that there is sure to be pushback, as there was when the airline industry announced baggage fees. “People went berserk, but the industry held its ground, and now about 30 percent of all air carriers’ revenue is non-fare related; in addition to bag fees, there are costs for extras such as drinks other than water, pets, and printing boarding passes. They’re moving to an à la cart menu model—you choose what you want, but pay for it.”

Morse maintains hoteliers should begin moving away from their risk-averse “this is the way it’s always been done” mindset. “As an industry, we need to take a stronger position so people don’t continue to take advantage of us. We have this valuable asset that requires daily cleaning, maintenance, and compliance with government regulations.”

He further stresses the need to experiment with changes such as those he suggests with their competitive position in mind, but urges them to do it sooner than later, while hotel occupancy is at its all-time highest levels. “Now is the time to be trying these things; it’s much harder during desperate times, like in 2009, when there was panic in the air.”

Morse admits he enjoys “shaking things up, rocking the boat” to counter the inertia he believes is endemic in the industry. “I think it’s a desire to change the status quo of doing things as they’ve always been done.” Yet, in a seeming contradiction, Morse advocates actually giving guests more bang for their buck through creative activations that engage the surrounding community as well as guests. “I subscribe to the European model; hotels there are gathering, meeting places more so than in America. What you want is for people to do more than come, sleep, and leave—you want them to come enjoy the experience at the hotel.”

Morse maintains that at nearly every price point, hotels can find ways to set themselves apart and become part of the memorable experiences travelers seek. “I love seeing people smiling, having a great time. When people feel the price you charge is reasonable and are having fun, the hotel is more than just a means to an end; it’s part of the story. Inculcating that sense of fun, that je ne sais quoi into the hotel experience is what it takes to get people to say ‘wow,’ and is what I myself enjoy most about the business.”