The tide of website accessibility lawsuits sweeping across the country shows no sign of receding. These lawsuits generally allege that a business’ website is not accessible to persons with disabilities in violation of Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and similar state and local anti-discrimination laws. Fueled in large part by the surge of website accessibility lawsuits, 2018 is bound to be another record year for the number of Title III ADA lawsuits filed across the country.

What is Website Accessibility?

Targeted business owners often wonder how they can be sued for having an alleged inaccessible website. After all, while Title III of the ADA covers a “place of public accommodation” (hotel, restaurant, retail store, etc.), neither Title III nor its implementing regulations define a website as a “place of public accommodation.” Furthermore, the U.S. Department of Justice, which is charged with enforcing Title III of the ADA, has not made website accessibility standards widely known. The concept of website accessibility, nevertheless, is developing in the courts through a patchwork of opinions.

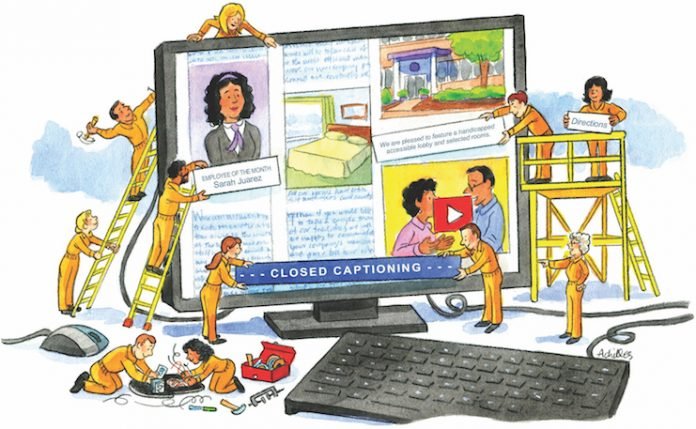

Website accessibility generally refers to the practice of ensuring that persons with disabilities can independently navigate, discern the contents of, and interact with a website. Common features include screen reader compatibility so the visually impaired can interact with a website, closed captioning on videos so that the hearing-impaired can understand the narration, and keyboard functionality so that the mobility-impaired—who may not be able to operate a mouse—can navigate the website with a keyboard.

WEBSITE ACCESSIBILITY

Website accessibility generally refers to making web content accessible to a broad range of people with disabilities, such as blindness and low vision, deafness and hearing loss, learning disabilities, cognitive limitations, motor impairments, and speech disabilities. There are several components to web development that impact web accessibility, such as content (the information in a web page), code (defines structure, presentation, etc.), authoring tools (software that creates websites), evaluation tools (test accessibility), and assistive technologies (screen readers, screen magnifiers, adapted keyboard, etc.) that allow users to independently interface with a website. It is important for a business to understand what goes into website accessibility so that it can implement a plan that is consistent with the emerging law and its needs and

resources.

There are no government-enacted website standards governing places of public accommodation. In the absence of government regulations, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 A and AA have emerged as the de facto standards for making websites and mobile applications accessible to persons with disabilities. Established in 2008 by a private consortium known as the W3C, WCAG sets forth four principles of accessibility (perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust) that are measured by various success criteria under three conformance levels (A—must satisfy, AA—should satisfy, and AAA—may satisfy).

WCAG 2.0, of course, is evolving with developments in technology. On June 5, 2018, the W3C published its anticipated WCAG 2.1 as a W3C Recommendation. According to the W3C, WCAG 2.1 builds on WCAG 2.0 and includes 2.0’s success criteria, such that web pages that conform to 2.1 also conform to 2.0. WCAG 2.1, however, also adds 17 new success criteria. The additions are intended to address three major groups: users with cognitive or learning disabilities (e.g., language and memory related disabilities), users with impaired vision (e.g., colorblindness, low vision), and users with disabilities on mobile devices (to keep pace with technological advancements since 2008).

Website Accessibility Lawsuits

Website accessibility lawsuits come in various forms. The majority of such lawsuits are filed by plaintiffs who are visually impaired. Allegations typically include that the website is not compatible with screen reader software and that it does not conform to WCAG 2.0 A and AA. (Time will tell whether it will become prevalent for complaints that allege non-compliance with WCAG 2.1 as well.)

As for lodging defendants, the complaints also usually claim that the plaintiff could not access services available online (view property locations, view room and hotel amenities, make reservations, purchase gift cards, etc.). They typically seek the following: an injunction to compel modification of the website to meet WCAG 2.0 A and AA; a declaratory judgment holding that the website is inaccessible; recovery of attorneys’ fees and costs; and, when available under state and local laws, damages.

Various causes of action are raised in website accessibility complaints depending on the forum and jurisdiction in which the action is filed. For example, typical federal claims against lodging establishments may include a violation of Title III of the ADA and/or a violation of Title II of the ADA—for instance, against a hotel convention center that is partly operated by a state or local government entity. As to monetary damages, the ADA limits recovery to attorneys’ fees and costs in private lawsuits.

Some states, such as California and New York, have adopted state and local laws (California’s Unruh Civil Rights Act, the New York State Human Rights Law, the New York City Human Rights Law, etc.), which have been deemed by some courts to govern website accessibility. Claims brought under such laws may subject a business to greater monetary exposure because, in addition to attorneys’ fees and costs, potential remedies include statutory penalties, compensatory damages, and punitive damages.

Developments in Website Accessibility Law

The area of website accessibility is developing in the courts on a case-by-case basis. The courts are split as to whether the ADA applies to a website and, if so, the applicable standard for compliance. The case law is trending toward the courts finding that the ADA requires that a business’ website be accessible.

For instance, in Haynes v. Dunkin’ Donuts, et al, No. 18-10373, the Eleventh Circuit recently revived a website accessibility lawsuit that was dismissed by the district court. There, the plaintiff, who is blind, alleged that he could not purchase gift cards online or access Dunkin’ Donuts’ physical shops, whose locations were listed online, because the website was incompatible with screen reader software. The Eleventh Circuit held that those allegations stated a plausible claim under the ADA because “the website is a service that facilitates the use of Dunkin’ Donuts’ shops, which are places of public accommodation.” The Court emphasized that the ADA applies to tangible and intangible barriers to access and, as such, “[t]he failure to make [online] services accessible to the blind can be said to exclude, deny, or otherwise treat blind people ‘differently than other individuals’” in violation of the ADA.

Businesses should prioritize enhancements to their websites, given the tide of website accessibility litigation and the potential to broaden their customer base. Here are some tips on how to identify potential barriers to access that may be present on your website, as well as how to fix them.

- Learn about WCAG 2.0 A and AA’s and WCAG 2.1’s success criteria and develop a plan to integrate those guidelines into your platform.

- Consult with counsel and technologists on best practices for web and mobile app accessibility.

- Develop a web and mobile app accessibility plan.

- Dust off your vendor contracts and consider adding or supplementing provisions on indemnification, representations and warranties, and limitation of liability.

Website accessibility litigation does not appear to be slowing down any time soon. Therefore, businesses should remain vigilant and take proactive steps to avoid being targeted.