In 1885, The New York Tribune assigned a reporter to investigate how many women unaccompanied by either a husband or parent were staying at four of the city’s largest hotels. According to the Tribune, the number was 44, and of that number, it can be assumed that many were actually full-time residents. That wasn’t all—according to the news story, “No woman traveling alone could find accommodations in any hotel unless she had an introduction or credentials and other evidence of her respectability.” Clearly, women traveling alone in the 19th and early 20th centuries could expect to encounter both mistrust and skepticism at hotels.

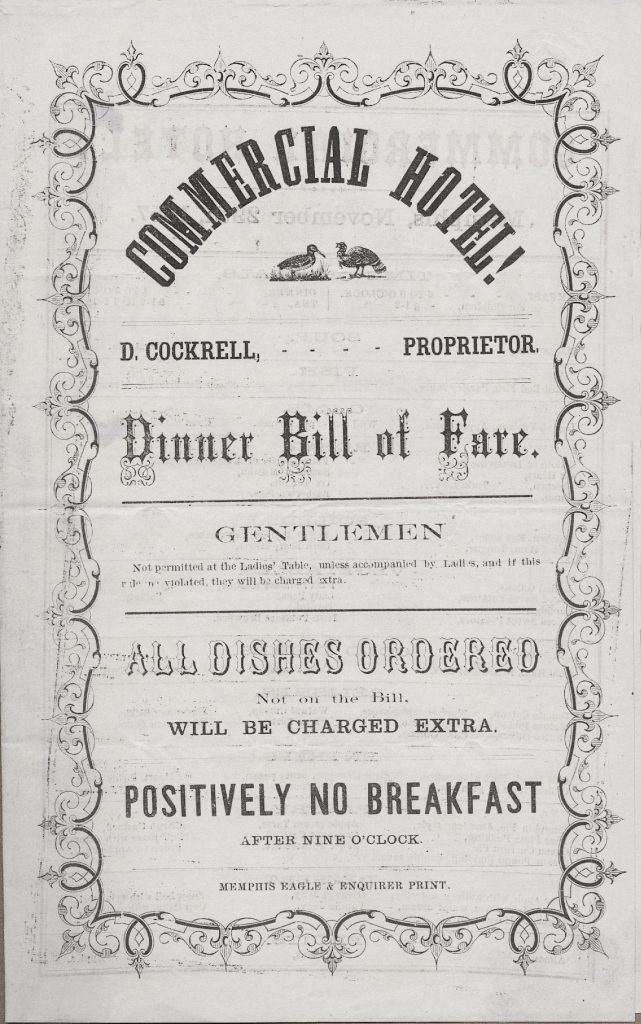

The idea of a woman traveling by herself was met with such suspicion that one early hotel historian noted, “A lady, unescorted, may sometimes be refused admission to a hotel by a plea of lack of rooms or some evasion of that kind.” It was suggested that the “lone woman” should “write or telegraph in advance; or, better yet, to take a note of introduction.” The dining rooms in most hotels were not much better. In the majority of hotels, there were separate dining rooms for men and women, or even separate dining times, which were often specified on the daily menu. Even as recently as 1932, one chef lamented the invasion of women into the male-only “Grill Room,” saying that men could no longer “look upon woman as on a pedestal.” He further complained that the women were now “smoking, drinking, and eating a different kind of food from what was formerly considered the women’s menu.”

The number of women travelers rose significantly in the first two decades of the 20th century. By 1930, women accounted for 30 percent of hotel guests and 50 percent of dining room patrons across the country.

In the early 20th century, however, there were accounts of some hotels that were willing to be more welcoming to female guests. One report in a 1908 issue of the Hotel Monthly showed that a western hotelier reserved front guestrooms for women to ensure they did not have to stay in rooms in the back of the building, which was in a less secure area of the hotel. In 1908, this may have been the exception, but slowly the industry began to change. In 1921, the Hotel Monthly describes the “Women’s Floor in Hotel McAlpin,” although over half of the article was about the children’s room and extended playroom.

What forced a change in the lodging industry? Changing times and profit considerations ultimately shut down these forms of discrimination. The number of women travelers rose significantly in the first two decades of the 20th century. By 1930, women accounted for 30 percent of hotel guests and 50 percent of dining room patrons across the country. Furthermore, when the Great Depression hit, hotels were reluctant to turn away any paying customer.

Reflecting the changing times, more hotels began to reserve rooms for potential female guests. In 1950, the Stevens Hotel—which already reserved women-only rooms—created a folder “For Women Only,” with stationary and information the traveling woman would find useful. By the 1980s, the various lodging trade publications contained articles all geared to the “new businesswoman” and what hotels could do to capture their business. Nowadays, no company would even consider shunning such a vital segment of the market.