William Shakespeare asked, “What’s in a name?” For U.S. hoteliers in the first half of the twentieth century, the answer was that hotel names should be evocative. Most had unique names; hotels in this period were often associated with a local person, such as the Davenport Hotel in Spokane, Washington, named for local restauranter and investor Louis Davenport. Some hotels were named after historical events or people, like the Hotel Patrick Henry in Roanoke, Virginia, named for the native son and revolutionary hero. Other hotel names are derived from nearby geographic features, like the Cataract Hotel in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Each hotel name conveyed a sense of pride and recognition to local institutions.

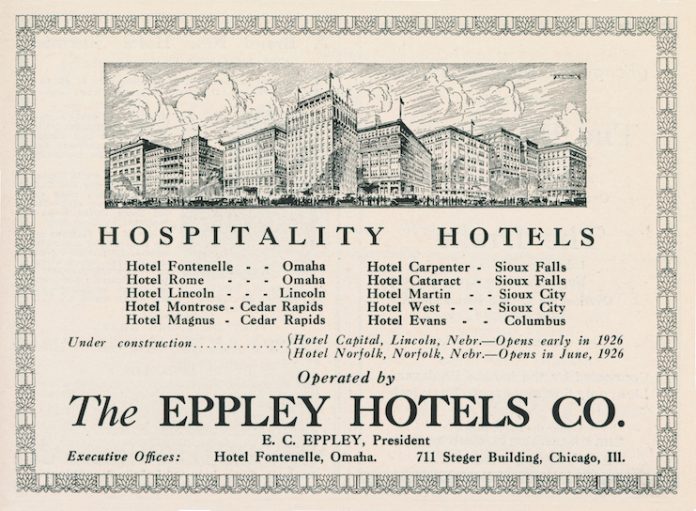

The first half of the twentieth century also saw the growth of the multi-unit hotel company. These companies either outright owned the property or the hotel lease, and usually continued using those local names as they acquired the hotels. For example, the Eppley Hotel Company, owned by E.C. Eppley and based in Omaha, Nebraska, operated several hotels across the Midwest. Yet individually, it was not clear these hotels belonged to the Eppley organization. Advertisements for Eppley listed the hotels by their individual names, often with an image of the hotel in the advertisement. Until he sold his hotels to Sheraton in 1956, all Eppley Hotels maintained their own individual names.

In a 1926 Hotel Monthly advertisement, Dinkler Hotels, which was based in Atlanta, listed six hotels in their stable of properties. While extolling that the six hotels Dinkler operated were “dispensers of true Southern hospitality,” they all had individual names. The advertisement also includes separate images of the properties to further underline the individuality of the hotels and their names. The public knew Dinkler hotels by their individual property names—the Andrew Jackson in Nashville, the Piedmont in Atlanta, or the Carling in Jacksonville, Florida—but not necessarily that they were Dinkler operated.

By the 1930s Albert Pick Hotels, a chain of Midwest and Southern hotels, advertised “Standardized Service” at their sixteen properties. Once again, those properties had unique and individual names. Other large hotel companies such as United Hotels, Milner Hotels, Affiliated National Hotels, and National Hotel Management Company followed this practice of individual hotel names.

The one hotel company bucking this trend was the Statler Hotel Company. Founded by Ellsworth Statler in the early 1900s, Statler hotels would lead the way in innovation and set the standard for the industry. All Statler hotels were large in size and popular with travelers. People knew what they could expect at a Statler hotel. Ellsworth Statler recognized that his name on a hotel was a selling point to the traveling public. After Ellsworth Statler’s death in 1928, the company continued to grow and maintained the Statler name on all properties except one; the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City was operated by Statler but owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, whose Penn Station was across the street.

The recognition of the Statler name—and the acknowledgment from a marketing standpoint of what a common name can do to enhance a product—slowly became accepted within the lodging business. A small Texas chain of hotels led by Conrad Hilton put the Hilton name on their properties from 1925 on. In the 1930s, a group of hotels in the northeast led by Ernest Henderson consolidated their properties with the name Sheraton. After World War II, Kemmons Wilson of Holiday Inns, Howard Johnson of the Howard Johnson Motor Lodges, and M.K. Guertin, founder of Best Western, all recognized the marketing power that a single name could deliver for their chains. Today, the lodging industry is chock full of recognizable brand names from coast to coast.

About the Author

Mark Young, Ph.D., is director of the Hospitality Industry Archives at the Conrad N. Hilton College of Hotel & Restaurant Management, University of Houston.